As a Rohingya refugee, I see a renaissance of my people’s culture in the Bangladesh camps

It is important that genocide survivors such as myself are not seen as merely victims, dependent only on others to take up our cause on our behalf

Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh are seeing a revival of traditional culture. ( Abbie Trayler-Smith/Oxfam )

At the end of last year, the Rohingya crisis gained renewed international attention when the Gambia faced off against Myanmar at the International Court of Justice over the genocide committed against my people.

It was a deeply historic and important moment, which was even watched in the refugee camps for displaced Rohingya in which I live in Bangladesh. Yet, as important as it was to see my former idol Aung San Suu Kyi in The Hague, this was a struggle between second and third parties, overshadowing developments that have been occurring within the Rohingya community itself.

I would like to share some of these developments for a simple reason: it is important that genocide survivors such as myself are not seen as merely victims, dependent only on others to take up our cause on our behalf.

The fuller Rohingya story is about much more than our collective suffering at the hands of Myanmar’s military. We are a people with agency, strength and resourcefulness, who seek dignity and meaning in our daily lives, just as others do.

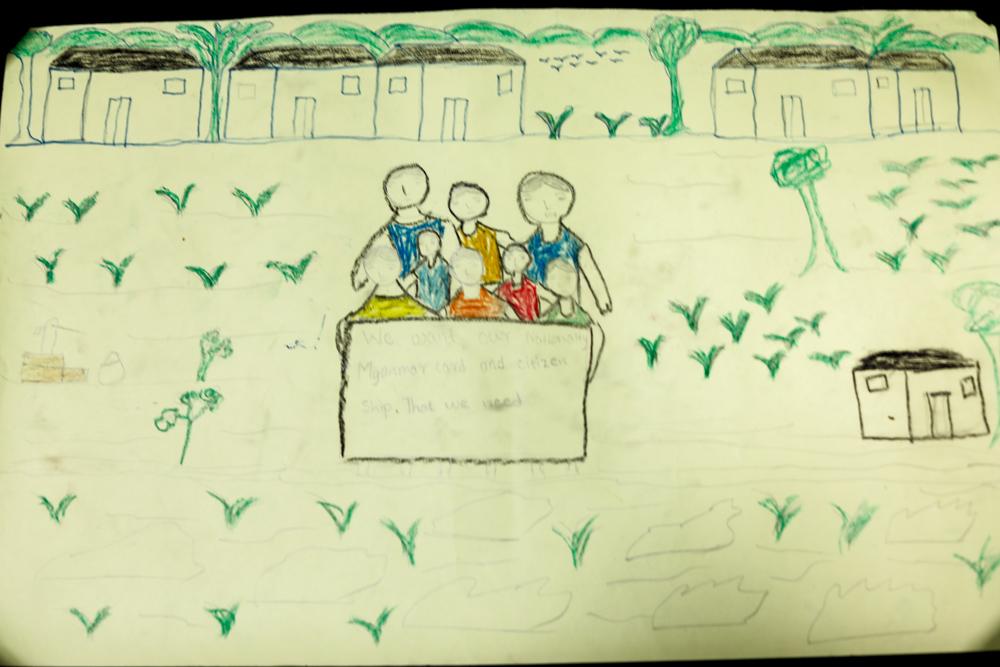

Created with Sketch. Drawings by Rohingya children

Show all 18

Created with Sketch. Created with Sketch.

The creative arts is an important medium for this, through which we also affirm our rights, heritage and identity.

You might not think that in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, one of the world’s largest refugee camps, we are living through a renaissance of the Rohingya culture. As we are forced to express ourselves in displacement and exile, the revival is bittersweet – nonetheless, it is taking place. As a genocide survivor in the camps, I am bearing witness to this every day. And it gives me some hope.

One example of this is the practice of calligraphy, which has long been a means of artistic expression for my people. In ancient Arakan, as our homeland Rakhine state is also known, Rohingya architects introduced the art of calligraphic curves into their designs. In the memory of the dead, Rohingya today inscribe calligraphy in Arabic and Persian scripts on the walls of their burial tombs.

Khari Irshad Hussain, a modern Rohingya calligrapher from Maungdaw Township, experienced the Myanmar military’s genocide against the Rohingya firsthand. On August 25, 2017, the military burned Hussain’s village to the ground, forcing him to flee across the Naf river to Bangladesh. He keeps the tradition alive, despite challenging conditions in the camps – he is still writing calligraphy on paper in his makeshift shelter. He is over a 100 years old now.

Music is also deeply rooted in Rohingya culture. In Arakan, musical instruments such as the Dab, Dhol, Bela, and many others were popular among Rohingya musicians. Songs like Zari, Kawali and Tarana are still popular among Rohingya.

Qawali is a devotional music popular in South Asia, which we also like to perform. One Rohingya man, Jafar Ahmed, was a master of the genre and fellow refugee, Nur Husson, was heavily influenced by his music.

In the past, Husson used to sing for weddings and religious events in Arakan and was well-respected. But now, he is forced to stay in Cox’s Bazar’s refugee camp, where, despite adversity, he still sings songs of praise and keeps the memory of our homeland alive through his music.

Poetry is another cherished form of expression that Rohingya keep close to their hearts. It has been a part of our culture for a long time (Shah Alaol and Dualat Kazi are considered two of the greatest 17th century Arakanese Muslim poets) and we still use it to this day.

In March 2019, we established a Rohingya online poetry website and Facebook group called the Art Garden Rohingya. So far, we have published more than 500 poems in English and Burmese. There are more than 200 emerging Rohingya poets, including women, who have been writing for the Rohingya Art Garden. Many of the poems are paeans to Arakan, their homeland. Others depict the long suffering many of us have experienced inside Myanmar and while fleeing to Bangladesh.

Poetry is also a force for solidarity and peace when it is shared with others. Last month I saw the power of poetry first-hand when I joined (via videoconference) a group of 39 other poets from different ethnic groups in Yangon. There were six of us in total from the refugee camp reciting our work.

Myanmar divided our communities by hatred but now, united through our written words, we can end the ongoing genocide against our people.

Mayyu Ali is the author of Exodus and co-founder of the Art Garden Rohingya

Comments

Post a Comment