Genocide’s straw man

- Get link

- Other Apps

Matthew Smith

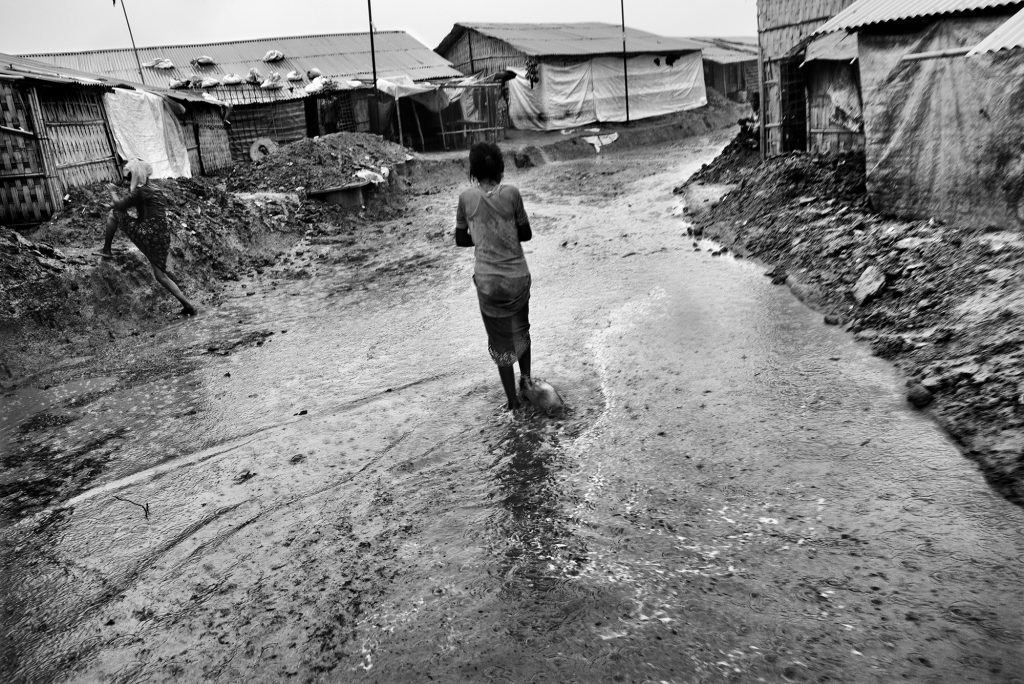

Rohingya camp in Cox’s Bazar // Greg Constantine

The Rohingya genocide in Myanmar has claimed tens of thousands of lives and displaced more than a million civilians, shocking the conscience of humanity and making the Rohingya a household name. A variety of individuals and institutions are responsible for the egregious situation, including the Myanmar military and police, civilian political elite, and extremist civilians, but in “Humanitarian Breakdown” (in the February 2020 issue), Benjamin Zawacki lays blame in a most unusual place: at the feet of the international human rights movement.

Zawacki is right to be profoundly disappointed that our world failed to prevent or stop yet another genocide. We are, too. But his understanding of the human rights movement and the way it works is deeply flawed. He not only fails to represent the work that human rights organisations actually did in response to the Rohingya genocide, but he misrepresents the way in which most human rights organisations operate and think about mass atrocity crimes. The result is a scattershot of classic straw-man arguments, ranging from the confused to the reactionary.

Unlike Zawacki, my colleagues and I have worked on the front lines of atrocities against Rohingya since 2012, documenting more than a thousand eyewitness and survivor testimonies, collecting detailed evidence, and using that evidence to prompt action. Rohingya advocates, our team at Fortify Rights, and other human rights organisations worked largely behind the scenes to prompt targeted sanctions against Myanmar’s military leaders, support an ongoing case against Myanmar at the International Court of Justice, help establish two independent UN bodies focussing on truth and accountability, spur an ongoing investigation by the Office of the Prosecutor at the International Criminal Court, and support a universal jurisdiction case filed in Argentinian court. Well-placed sources informed us that these moves towards accountability worried the Myanmar military elite and affected their decision-making — which was, to an extent, precisely the point. On the Bangladeshi side, the work of human rights defenders prevented both forced returns of Rohingya refugees to Myanmar and forced transfers of refugees to a flood-prone island, and more recently led the Bangladeshi government to finally allow some Rohingya youth to attend school in refugee camps.

While more needs to be done, none of this appears to matter much to Zawacki, a colleague and friend who worked for Amnesty International from Thailand for five years. He acknowledges at the outset of his polemic that “the Rohingya would be even worse off” without the human rights movement — a claim he doesn’t explain. Instead, he goes on to outline our “collective failure”.

Clarifying that his ire is towards “regional or international” human rights organisations “working partly or exclusively on Asia or Southeast Asia”, Zawacki complains that NGOs devote the same amount of resources to genocide as they do to lesser violations. “An ongoing project on human rights defenders or cyber laws,” he writes, “might therefore receive as much attention as the targeted slaughter of thousands.” He cites no evidence to back up the claim.

While I cannot speak for the six other international human rights organisations named in his article, Zawacki did not request information about our internal allocation of human and financial resources to the Rohingya crisis, nor apparently did he review our website, which shows that since our founding in 2013, we’ve published eighteen full-length investigatory reports on human rights situations in three countries — Myanmar, Thailand and Malaysia — half of which focus on violations against Rohingya. Moreover, since March 2017, we’ve created thirty-six films, sixteen of which focus on Rohingya.

We’ve also convened and supported Rohingya advocates, including women; testified before US Congress; briefed the White House under two administrations; met Asian heads of state; and lobbied UN member states with Rohingya colleagues, among other strategic actions. Needless to say, we don’t have all the answers, but we do evaluate the seriousness of the situations in which we work, and we allocate resources accordingly.

Zawacki implausibly suggests that “human rights NGOs reached their apex of prestige and influence in the 1990s”. In reality, the 1990s were empirically the apex of violence and death. The Uppsala Conflict Data Program, widely regarded as a leader in the collection of datasets on violence and conflict globally, shows that the 1990s were actually the deadliest decade between the 1980s and 2020 in terms of “fatalities in one-sided violence”, defined as “lethal attacks on civilians by governments or formally organized groups”. This is true even excluding the Rwanda genocide.

If the effectiveness of human rights organisations has declined since the 1990s as dramatically as Zawacki claims, then it would stand to reason that the world would be more violent now than it was then, and that there would be more, not less, genocide. But that’s not the case. In her book Evidence for Hope: Making Human Rights Work in the 21st Century (2017), Harvard professor Kathryn Sikkink cites events-based data to demonstrate a global decline in genocide and politicide (noting with sensitivity that such a decline “offers no comfort” to survivors of current genocides).

“Whether we use episodes or try to count actual deaths,” Sikkink writes, “evidence supports the conclusion of a decline in one-sided violence in the world.”

Sikkink’s survey of current data “suggests that overall there is less violence and fewer human rights violations in the world than there were in the past,” and she outlines a number of areas in which positive changes are due to the work of human rights defenders and “human rights law, institutions, and movements”.

In short, while we cannot gauge with 100 per cent certainty the impact of the human rights movement, empirical data doesn’t support Zawacki’s claim that human rights organisations were at their apex of effectiveness and influence in the 1990s.

It’s worth noting, also, that human rights organisations were much fewer in number in the 1990s and had less access to people in power, fewer financial and human resources, and less technical ability to reach the masses. Colleagues who documented and exposed atrocities in that decade recall the snail’s pace of advocacy: manually printing reports and physically mailing them to embassies and governments, often waiting months for replies.

In The Justice Cascade: How Human Rights Prosecutions are Changing World Politics (2011), Sikkink uses data to demonstrate that criminal accountability for human rights violations — achieved through the work of human rights defenders — is associated with improvements in human rights practices. This runs contrary to critics who claim, without data, that accountability in situations of mass atrocities is futile or that it threatens peace.

Indeed, the spectre of accountability for perpetrators of atrocities in Myanmar doesn’t resonate with Zawacki. He breezes past the Human Rights Council’s 2018 establishment of the Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar, which was created in turn following the work of the UN Fact-Finding Mission. Zawacki fails to mention this mission, let alone the coordinated work of the human rights movement that led in large part to its creation in Geneva in March 2017, six months after the first wave of violence against Rohingya began. While Zawacki casually concedes that counterfactuals are impossible to prove, Sikkink’s data and analysis suggest in concrete terms that both accountability mechanisms created by the Human Rights Council (the body with “jaw-dropping deficiencies”, according to Zawacki) as well as future prosecutions would lead to better outcomes for the people of Myanmar.

Zawacki goes on to suggest that human rights groups are ineffective today because they “persist in believing there is one ‘international community’”. This is also confused. It’s true that the occasional human rights publication mentions “the international community”, but Zawacki would be hard-pressed to find a single human rights defender anywhere who believes the world comprises a singular and monolithic “international community”. Experienced advocates have a deep and detailed understanding that each government has its own unique pressure points, personalities and priorities, and they work accordingly.

Almost laughably, Zawacki argues there is not a single “international community”, but rather two: China and countries it defends and supports, and the rest of the world. He continues, with a non-sequitur, that NGOs’ “primary strategy”, which he identifies as “naming and shaming”, is now ineffective with “errant countries” like China that feel no shame. He argues that documenting and exposing human rights violations — no easy task — is now a waste of time, because China and its allies reject and attempt to bury the truth.

Wouldn’t government rejections of credible evidence of human rights violations mean that documenting the truth is even more critically important, or are we to succumb to a post-truth world? How would that prevent genocide?

Moreover, “naming and shaming” is, according to Zawacki, a “media heavy” strategy, and he claims it is now ineffective because of changes in the media industry. “The proliferation of blogs and web-based outlets,” he writes, “has come at the expense not only of journalism’s quality and reliability but of its power to focus global attention, even on genocide. The news cycle’s replacement by a 24/7 torrent has rendered even focussed attention short-lived.” Once again, Zawacki points to the glory days of the 1990s, when, he suggests, the news media focussed sustained global attention on genocide.

Zawacki also focusses on what he calls human rights organisations’ “social media obsession”. Using social media to advocate for human rights is a waste of time, he argues — again, without data — because governments don’t listen or pay attention to it. He then acknowledges that certain governments use social media to target human rights defenders, contradicting his claim that governments ignore the medium.

Regardless of the degree to which governments are shamed via social media, the medium has many uses and tweeting at authoritarian governments is hardly the only function it serves. We also use it to communicate about abuses to the world at large to create broad coalitions to stop abuses and inform policy. Clearly Zawacki is aware of these other uses for social media because he shared his article via Twitter; the irony is not lost on us.

Zawacki also claims that human rights organisations “devote insufficient resources to China”. I agree with him in full that there should be more attention on China with regard to human rights. Zawacki goes a step further, however, suggesting — again, without data — that human rights organisations in practice devote the same resources to all countries regardless of the scale of abuse present there. “Brunei is not China,” he writes figuratively, “as plainly as a detained journalist is not genocide.” But do human rights organisations really devote the same resources to China — in terms of investigations, advocacy and other work — as they do to a figurative Brunei? The answer is no, they do not.

It’s not until the end of the article that the reader is introduced to Zawacki’s “chief reason” why the human rights movement failed the Rohingya. “Human rights NGOs should have called for the use of force in Rakhine State,” he writes, arguing for military intervention against Myanmar’s armed forces. He goes on to make the incorrect and garish claim that human rights groups were willing to “accept the killing of thousands of Rohingya civilians than venture action likely to claim the lives of far fewer Myanmar soldiers”.

Zawacki argues that NGOs should have made the responsibility to protect (R2P) “the subject of a call to action” favouring military intervention in Rakhine State to stop the genocide. My colleagues and I are not opposed to R2P or UN Security Council action to protect human rights, and military intervention should remain up for discussion as a last resort. However, R2P explicitly requires any such intervention to be approved by the Security Council — which Zawacki correctly acknowledges is corrupted by China’s veto — even if other powerful members backed the idea, which they didn’t. I briefed the Security Council in New York in September 2017, having arrived from the Bangladesh–Myanmar border while attacks against Rohingya in Myanmar were ongoing. There was zero interest in military intervention. Any call for an R2P-based military intervention into Rakhine State in 2017 was dead on arrival.

If China would have vetoed an R2P intervention, then what exactly is Zawacki arguing for? In essence, Zawacki wishes NGOs had called for an intervention into Myanmar that was not approved by the Security Council and thus in violation of international law, following the example of NATO’s bombing campaign in Kosovo in 1999, which was “illegal but legitimate”. This time, however, Zawacki has concluded that an intervention into Rakhine State “would have been legal because it was legitimate”. This argument ignores the law as well as the history of military intervention.

Zawacki himself refrained from publicly calling for military intervention during the genocide. Seven days after the second wave of the genocide began, on 2 September 2017, he told Al Jazeera that Myanmar State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi should allow human rights investigators to access Rakhine State, adding, “Until or unless she and the military are able to see a peace process in Rakhine State as encompassing more than a military solution, we are likely to see more of what we’ve seen this past week.” His solution at the time was to call for more human rights monitors.

Nevertheless, Zawacki beseeches NGOs to be more political in their engagements — more practical in how they spend their resources, more utilitarian in their approach, and more realistic about impacts and outcomes. Yet his argument in 2020 for a military intervention in 2017 is devoid of political realities. The world has zero appetite for military intervention in a hostile country that is backed by a permanent member of the UN Security Council. NGOs didn’t avoid calls for military intervention because of a vague fundamentalism against it, as Zawacki claims, but rather because it was simply unwinnable, and time was of the essence.

Moreover, Zawacki never details what a military intervention in Rakhine State would have looked like. He doesn’t explain which government might have taken the lead, or how it could’ve been done without igniting World War III, as China would have likely responded by deploying forces to protect its multibillion-dollar investments in Rakhine State’s energy sector.

Zawacki doesn’t bother with these war-game scenarios — that’s a luxury those on the front lines can’t enjoy.

Comments

Post a Comment