Harn Yawnghwe, An Extraordinary Life in Public Service & A Barricade Against the Erasure of the Shan from Myanmar’s Memory

This is the first of the three part semi-biographical long read.

Yawnghwe family photo, (with several other siblings, absent) (circa., early 1950’s).

Source: Sao Sanda (2008) The Moon Princess: Memories of the Shan States, River Books, Bangkok.

Exterior of the Shan Palace Museum, Yawnhwe, formerly the royal palace.

The eastern staircase, guarded by two nagas.

This is a story of a young Shan prince from my native Myanmar who “played” with Chairman Mao in the Forbidden City and proceeded to became one of our country’s most prominent exiles, having devoted half a century of his life to public service, with personal integrity and guided for his Christian faith.

Yawnghwe Family home, Haw in Shan (palace).

Source: Sao Sanda (2008) The Moon Princess: Memories of the Shan States, River Books, Bangkok.

Harn, 4th from the left, in puffed up Chinese cotton coat, first row, with his two older brothers Mie and Eugene to his immediate right, accompanying his father’s official state visit to China, hosted by Chairman Mao, the Forbidden City, 4 May 1957. (photo courtesy of Harn Yawnghwe)

The photo above is historic and speaks volumes about the tremendous role the Shan people played in the 1,000 years of history of Myanmar’s emergence as a cohesive political state.

Let me begin by creating a comprehensive caption.

Source: Sao Sanda (2008) The Moon Princess: Memories of the Shan States, River Books, Bangkok.

His mother Mahadevi (Chief Queen) Sao Naw Kham, then Speaker of the Upper House of Myanmar’s parliament and, after the 1962 coup, a founder of the Shan State Army (SSA), was right behind hand, to the right of Chairman Mao and, to Mao’s left was his father President Sao Shwe Thaike, who died in the coup junta’s captivity months after the 1962 coup led by General Ne Win.

One older brother, to his immediate right, named Sao Myee, then a teenager, was killed in a pre-dawn coup raid at their residential compound by General Ne Win’s troops, on 2 March 1962. Harn and Myee shared the same bedroom on the 1st floor of their mansion in Rangoon, from which the latter sprinted to the front door where he was shot and killed instantly. The next thing Harn saw was his closest older brother lying in a pool of blood, just outside the front door.

Another brother Eugene Thaike, in glasses, second from the left, front row, (full Shan name with the royal title: Chao Tzang) became a university tutor in English Department at Rangoon University at the time of coup and later joined the Shan resistance against the anti-federalist Myanmar junta and assumed a commandership of the Shan State Army (SSA). Ahko Eugene (Elder Brother Eugene),as I called the former revolutionary and Marxist-inspired intellectual, with affection and admiration, succumbed to brain cancer in exile, in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. He earned his doctorate from the University of British Columbia with the comparative analysis of Indonesian and Myanmar authoritarian systems.

Far left in the front row is his older sister Sao Ying Sita, a writer and journalist for a major US publication, and a classmate of Aung San Suu Kyi at the elite Methodist High School in Rangoon. (photo courtesy of Harn Yawnghwe). When Harn accompanied the then Chair of the Karen National Union ex-general Mutu Sei Paw to the latter’s meeting with Aung San Suu Kyi, then serving as the State Counsellor, or de factor head of Myanmar, the first thing she asked was, “How is Ying doing?”. Sao Ying is in late 70’s or even early 80’s, afflicted with some old age illness in an assisted living home in Thailand while Suu Kyi herself is in the coup regime’s captivity, held incommunicado, somewhere in Naypyidaw.

At the time of the 1st military coup in 1962, Harn was a teenager (14 at the time). Consequently, Harn escaped to Thailand with his politician mother, via Rangoon-Moulmein train and later by specially arranged overland transport to the Thai Burmese border, the usual escape route for dissidents. They left behind the ex-president, husband and father, in Ne Win’s VIP jail in Rangoon, who subsequently “died of natural death” behind bars, as Harn put it to me some years ago.

The mother and son made their way to Northern Thai city of Chiang Mai.

Like the Kurds in West Asia, Shan or Dai or Thai people as an ethno-linguistic group are scattered across different highlands, before European colonizers introduced and instituted hard borders for their “colonial possessions”. The Shan of South Asia and Southeast Asia inhabit Assam of N. East India, Laos, Thailand, China and perhaps other parts of mainland Southeast Asia. This was also true of Myanmar’s other pre-nation-state ethnic groups including Karen, Kachin, Chin, Rohingya, Rakhine, Karenni and Mon.

In the Siamese or Thais view the Shan of Eastern Myanmar as their anthropological kin. The Thais call them as Tai-yai, or Big Brother Thai.

Rama IX, the unofficial host and patron of Harn and family during their stay in Thailand

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bhumibol_Adulyadej

The then American-born King of Thailand Bhumibol Adulyadej (1927-2016), titled Rama IX, evidently offered Harn’s royal mother Sao Naw Kham, his sister Sao Ying and himself a refuge. Harn remembered a Northern Thai businessman with a known tie to the monarch in Bangkok, paying a visit to his mother not long after their arrival in Chiang Mai, an old seat of kingly power in Northern Thailand known as Lana Thai.

They were provided with accommodation and legal protection in Chiang Mai. .The businessman brought a pistol and a round of munition, and left them with Harn’s mother, with one clear advice, “Just shoot”. …. That is, in the event of a life-threatening situation. In those days General Ne Win was widely known to send teams of assassins to eliminate his political opponents, communists or non-Bama ethnic resistance leaders. Among the best-known victims were the Karen National Union leader and Cambridge-educated barrister Saw Ba U Gyi and the Leader of the White Flag (Maoist) Burma Communist Party (BCP) Thakhin Than Tun, both peers of the martyred General Aung San, Aung San Suu Kyi’s father. Than Tun was Aung San Suu Kyi’s uncle.

From her exile in Northern Thai province across her native Shan state, Harn’s widowed mother was subsequently involved in founding the Shan State Army (SSA). Already her oldest son, Harn’s oldest brother Eugene, had joined the Shan underground, following General Ne Win’s coup of 1962, and subsequently became a SSA commander.

As for Harn, he resumed his high school studies, which was interrupted by the coup back in Rangoon and the resultant political turmoil into which his political family was thrown. Because Shan and Thai languages have so much linguistic overlaps –like Myanmar and Rakhine languages – Harn quickly picked up the Thai dialect. After completing his high school at a Christian missionary school known for its academic rigour, Harn was admitted to the royally patronized Chulalongkorn University where he did his undergraduate studies in engineering, in the late 1960’s. As he put it, “without any national identification card or proper papers”. With good reason, he suspected that the Rama IX continued to look after his family.

By then the older brother Eugene, former university tutor-cum-SSA commander, joined the family in Chiang Mai, with his Shan wife. In those days, Myanmar military strategists were using the colonial ethnic divide and rule strategy in order to weaken, contain and crush its main nemesis in Shan state, specifically genuinely Shan nationalist movements, with left and right ideological orientations. Specifically, General Ne Win weaponised the Kokant militia, led by Eastern Myanmar-born Han Chinese and mixed Sino-Shan against several Shan armed organizations including the SSA, who were genuinely interested in political autonomy and a federalist state of Myanmar. The Kokant militia were primarily an armed commercial organization, involved in heroin production, transport and trade. According to ex-Captain Thant Zin Myaing, a former aid-de-camp to the Chief of Staff the late General Tin Oo (co-chair of the National League for Democracy party), whom I interviewed for my doctoral thesis on Myanmar military dictatorship in the United States in the fall of 1994, General Ne Win, the head of the junta, allowed the Kokant militia a free reign in their narco-economy in exchange for intelligence gathering on and disruption of the anti-junta resistance activities of SSA.

A group of exiles from Myanmar at a political retreat in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, USA, Jan. 1999:

Front Row on the floor, from left to right, Dr Thaung Tun and Harn Yawnghwe (both with the now defunct US-based National Coalition Government of the Union of Burma or NSGUB); Second Row seated on sofas, from left to right. Maureen Aung Thwin, then Director of the Burma Project, Open Society Institute, George Soros Foundation; University of Illinois Professor Laran Maraw, (bespectacled) Dr Eugene Thaike (aka Chao Tzang Yawnghwe and Naw May Oo Mutraw, now the advisor to the Karen National Union (photo by Zarni).

Harn’s brother Eugene got out of the messy revolutionary politics in time before things turned for worse in this triangle of the drug militia, the Shan nationalist movements and the US-backed Ne Win’s military. As a matter of fact, Eugene narrowly escaped the assassination attempt in Chiang Mai at the roadside, at the spot where the popular upscale Nimman Shopping Mall stands today. The assassin’s bullet hit and instantly killed the motorcyclist, instead of Eugene, who sat on the passenger’s seat behind, and the motorcycle fell into a ditch nearby. The shooter, himself, was on the motorcycle, and wrongly assumed he hit the target, Harn’s brother. The incident prompted the family to relocate to Canada, further away from the long arm of Ne Win’s junta and its affiliates.

Harn (3rd from the left, with his left knee on the concrete floor, wearing a Chinese cotton coat), with Prime Minister Chou Ein-Lai (the second row, standing with his locked hands folded, flanked by Harn’s mother and father President of Burma Sao Shwe Thaike, bespectacled and in pinstripe business suit).

Forbidden City, Beijing, 4 May 1957 (photo courtesy of Harn Yawnghwe)

The two black and white photos with the Chinese leaders were taken in less than 5 years before the family was thrust into both political and personal turmoil by General Ne Win’s unwarranted military coup of 1962. As it were, the photos captured the calm before the storm that would wreck their life as a leading Shan family fighting for ethnic group equality in the post-colonial Union of Burma.

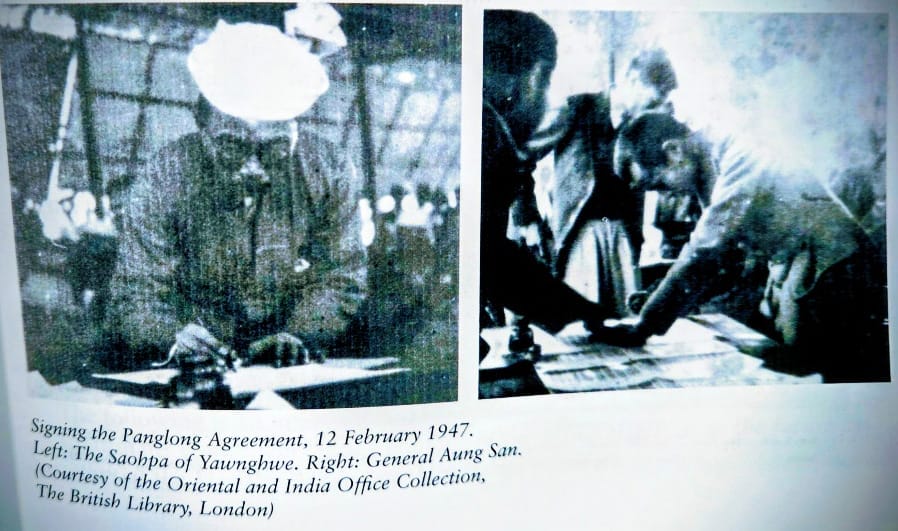

The ethnic group equality among Myanmar’s diverse ethnic communities with differing historical memories, distinct cultures and identities and mutually incomprehensible languages among several major groups that have shaped the historical trajectory of what became a nation-state of Burma or Myanmar was the promise that Myanmar’s sole representative (ex)-General Aung San made.

After the British-involved assassination of General Aung San on 19 July 1947, just months before Britain’s formal transfer of sovereignty to Myanmar, the Bama or Myanmar nationalist leaders who succeeded Aung San’s mantle reneged on this pre-independence pledge which was openly enunciated in Panglong Agreement or Treaty (among several major ethnic groups). Harn’s father was a key host which helped midwife this power sharing blueprint for future Burma, post-British rule.

It was fitting that post-Aung San’s death on 19 July 1947, Sao Shwe Thaike assumed the inaugural presidential post, and presided over the independence transfer ceremony at the Government House in Rangoon at 4:30 am on 4 January 1948. While the two treaties – Aung San-Atlee and Nu-Atlee – were signed in February and October 1947, effectively paving the foundation for the end of 120+ years of British rule in pre-nation state of Myanmar, the formal independence ceremony was held the following year, which was calculated by the country’s Brahminic fortune-tellers as astrologically auspicious for a peaceful and prosperity Union of Burma.

Alas, not only the nearly eight decades of Myanmar’s political history have proven how incredibly wrong these star-based projection of the superstitious country’s future has been, but also the seismic political events have come to shape the lives of Myanmar’s political families, as much as the country’s public.

Harn’s father Sao Shwe Thaike (on the far right), the inaugural President of the Union of Burma, presiding over the sovereignty transfer ceremony, Government House, Rangoon, 4 January 1948.

Source: Sao Sanda (2008) The Moon Princess: Memories of the Shan States, River Books, Bangkok.

Harn’s extraordinary life of seven decades cannot be understood, much less appreciated, outside this broader context of national and exilic politics of Myanmar. His late father, a leading Federalist, died in Ne Win’s jail in 1962 while to striving to realize the original federalist design as the only viable form of political state with diverse Both his politician mother and revolutionary brother died in exile, in Canada, having never set their feet on the soil of their ancestors who helped build what became the nation-state of Myanmar.

Harn Yawnghwe, during a consultation meeting hosted by the Indonesian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Bali, Indonesia, March 2023 (photo by Zarni)

Importantly, Harn has “inherited” the family’s legacy and project of striving for federalism – that is, ethnic group equality for all, and has had a remarkable run of almost half-century in the country’s political affairs. The federalist project and a peaceful Myanmar is something which he has pursued with characteristic calmness, diligence and integrity, at the very least, over the three decades I have known him.

We don’t necessarily agree on everything. We came from different ethnic, faith and political backgrounds. But I have come to see my fellowship of the two exiles who have jettisoned our/their professional careers, as a healthy, respect-based democratic relationship, based on a shared desire to see our birthplace break free of this vicious cycle of overly ethnic politics, devoid of ideals and principles, or empathy, violence and mistrust.

Beyond wishing to tell and record a life story of a fellow democrat in exile, with whom I have known and worked since 1996 when we first met at a Burma event in New York City, I approach my written words here as one Bama’s deed, if long overdue, of rectifying the historical wrong perpetrated against the Shan peoples by the ruling Burmese or Bama or Myanmar whose name the country bears, whether it is Myanmar or Burma.

Source: Sao Sanda (2008) The Moon Princess: Memories of the Shan States, River Books, Bangkok.

Specifically, the civilian politicians, the patriotic Bama intelligentsia and, certainly, successive military leaderships bear the primary responsibility for our dominant ethnic group’s collective crime of erasure.

That is, the erasure of the crucial roles the Shan of different ideological orientations, left and right, have played in midwifing Myanmar as a federal union of equal ethnic communities that voluntarily joined hands in order to forge a peaceful post-colonial nation. In this erasure, names of historical figures of epic proportions as well as their personal stories of sacrifice, love of the multiethnic political entity that came to be called the Union of Burma and, since 1989, Myanmar, have largely vanished.

While the focus of my three-part essay here is Harn Yawnghwe, one living figure, a friend and a comrade, this act of truth-telling must be extended to other similarly noteworthy figures from different ethnic and faith backgrounds whose contributions must not be consigned to the footnote of Myanmar’s national history.

I have taken opportunities to re-insert the important historical details which our own Bama nationalists, both civilian democrats and autocratic military rulers, have airbrushed out of popular memory and official history of Myanmar. Contributions of Myanmar Eurasians (for instance, James Barrington, the country’s first ever ambassador to the United States), Myanmar of Chinese and Indian ancestral origins (for instance, MA Rashid, U Pe Khin, U Win, Taw Sein Kho), other non-Bama ethnic people, Muslims and Rohingyas as well as anti-junta communists, must be re-inserted in the country’s history.

Truth is effectively a basis of peace and reconciliation in all multiethnic and racial politics. A healthy, humane and harmonious nation cannot be built on lies, omissions, and distortions, no matter how great the temptation is to retain only the rosy memories to corroborate one’s nationalist aims and virtues.

I penned this piece not simply to record a remarkable life that my fellow exile and comrade has led over the last half-a-century, first as a 20-something university student at Canada’s prestigious McGill University in Montreal, where he began his exilic activism by publishing Burma updates and reaching out to other fellow exiles from Myanmar, but also to encourage others to record and share similar cases of erasure of contributions by the non-Bama ethnic peoples and personalities to post-colonial nation building.

It matters not that their/our efforts over three generations now have not come to fruition. What matters is that we keep an honest historical record-keeping. For not to acknowledge heroic and admirable efforts, irrespective of the outcome, is, in my view, an act of intellectual dishonesty, especially as members of the dominant ethnic group.

“Forgetting is a crime,” wrote the globally acclaimed exilic Czech writer, the late Milan Kundera. Erasing important historical details is hence a greater crime still.

The focus of the next part of this essay will be on the formation and trajectory of this exilic figure, and how his chosen faith – Christianity – guides his politics and thoughts. The final concluding part will be on the erasure of Shan as a people and a national community, and their historical and political contributions to the emergence of Myanmar’s political systems.

Maung Zarni

Comments

Post a Comment