Hollowed Out “Never Again!” and the Collapse of Europe’s Moral Imagination

Europe, and Germany in particular, postures as the moral conscience of the postwar world.

No society has invested more intellectual and institutional energy in confronting its crimes than Germany has with the Holocaust. Yet faced with the mass death, forced displacement, and systematic destruction of life in Gaza, Europe has responded with paralysis, euphemism, and procedural caution. This contradiction is not incidental; it exposes the fatal limit of Europe’s moral imagination.

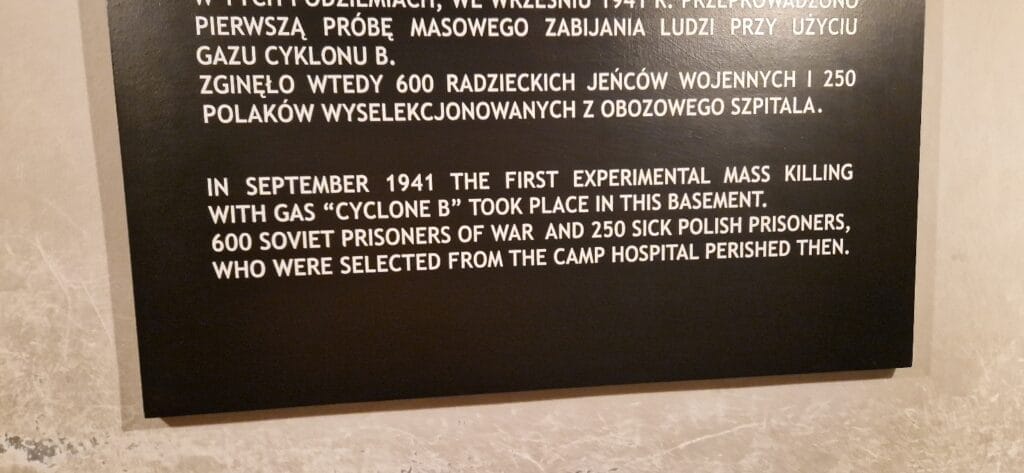

The building on the left is the infamous Block 11, and the large building with red tile roof was the original storage facility for gas “Cyclone B”, now the home of Education Division, Auschwitz I. (photo by Zarni, Oct. 2023)

Germany’s postwar settlement rejected inherited collective guilt but embraced an eternal responsibility. Holocaust memory was cemented into law, education, and political culture, culminating in the doctrine that Israel’s security is Germany’s Staatsräson—a national reason of state. This commitment was intended to prevent the repetition of past crimes.

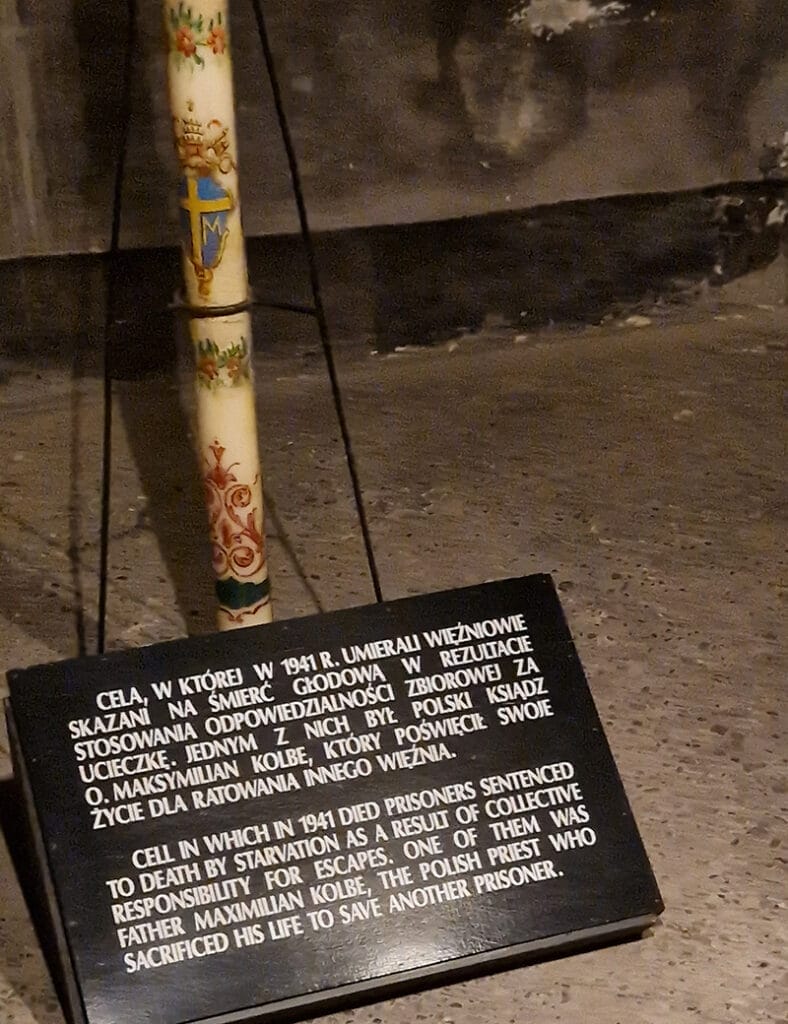

A cell in the infamous Block 11, Auschwitz I. (photo by Zarni, Oct. 2023)

Instead, it has produced a rigid ethical framework, one that fails to recognize injustice when it falls outside the specific historical template of the Third Reich. The problem is not ignorance of Palestinian suffering, but a moral architecture never designed to perceive it.

Frantz Fanon, in The Wretched of the Earth, argued that colonial violence is not exceptional but structural. It does not manifest as a rupture demanding moral reckoning, but as a condition to be managed. Civilian deaths under occupation are rendered tragic yet tolerable, regrettable yet inevitable. Order is privileged over justice; stability over liberation.

Europe’s response to Gaza is, from this perspective, grimly predictable. Palestinian suffering is processed as a humanitarian problem, not a political emergency. Aid is debated; accountability is deferred. Violence is condemned rhetorically while the structures that enable it are insulated from critique. As Fanon warned, colonial violence becomes invisible precisely because it is continuous.

Edward Said’s critique of Orientalism further explains why this suffering fails to command full moral recognition. Within dominant European discourse, Israel is legible: a familiar, Western-aligned state—strategic, rational, juridical. Palestinians, by contrast, appear as emotional, opaque, and threatening; their voices are treated as advocacy rather than testimony. This discursive asymmetry determines who is believed, who is mourned, and whose deaths require justification before they can elicit outrage. Even when acknowledged as victims, Palestinians are rarely recognized as full political subjects with legitimate claims. They remain objects of concern, not bearers of rights.

Germany’s particular paralysis sits at this intersection. A Holocaust memory, rightly treated as singular, has hardened into a moral firewall. Any forceful critique of Israel is instantly scanned for historical inversion: Germans judging Jews, perpetrators lecturing victims. Faced with this specter, German policy defaults to the least destabilizing position—verbal concern paired with material and diplomatic continuity. This is not unconscious guilt; it is overcorrection institutionalized as doctrine.

As philosopher Zahi Zalloua argues, ethical frameworks collapse when they trap us in fixed identities: absolute victim, absolute perpetrator, moral debtor, moral creditor. Ethics must be relational, responsive to present vulnerability, not frozen in historical accounting.

Europe’s moral language remains backward-looking, Neanderthal and categorical. It asks whether today’s violence fits yesterday’s template, whether suffering meets inherited thresholds, whether recognition risks odious comparison. In doing so, it forecloses ethical responsiveness. Palestinian suffering becomes legible only insofar as it confirms established roles.

This is also why the word genocide is so meticulously avoided. The hesitation is not merely legal; it is imaginative. In European memory, genocide is industrial, bureaucratic, unmistakable—evil in a recognized form. Violence that unfolds through siege, starvation, and asymmetric warfare does not “look right.” It is reclassified downward, managed linguistically, and stripped of its power to rupture moral comfort.

What we are witnessing, therefore, is not a failure of memory, but a failure of universality. “Never Again” was never operationalized as an ethical principle capable of restraining allies or confronting colonial logics. It became a promise bounded by geography, history, and power.

This is why the current moment is so profoundly unsettling. The images are ubiquitous; the suffering is documented in real time. The justifications—complexity, lack of leverage, fear of escalation—sound dreadfully familiar. What returns is not the psychology of genocide, but the logic of the bystander, now wrapped in the sterile language of humanitarianism and legal caution.

Former perpetrators, Europe does not lack lessons. It lacks the courage to apply them.

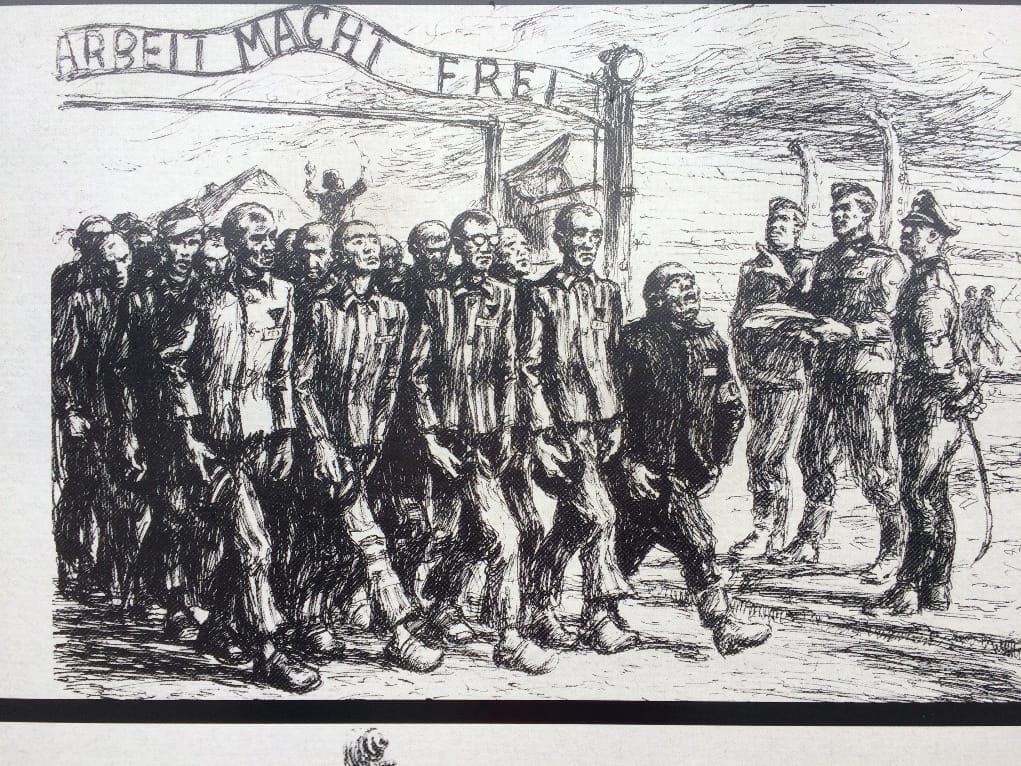

The illustration of prisoners’ march through the iconic entrance at Auschwitz I as the SS guards watched with whips in their hands (Photo by Zarni, March 2017)

Until Holocaust memory is integrated with a full reckoning of colonial violence, and until moral imagination is freed from fixed identities and geopolitical loyalty, Europe will continue to remember the past with solemnity while failing the ethical tests of the present.

“Never Again” will remain a commemorative slogan, not a living ethic—invoked sincerely, yet constrained by the very structures it was meant to overcome.

Indeed.

Former Israeli Occupation Force (IOF) captain and now Professor of genocide history at Brown University, Omar Bartov, put it,

“(i)n terms of the whole culture of memory, commemoration, teaching, pedagogy that use the Holocaust with very good intentions to teach tolerance and humanity — that is becoming increasingly difficult now because those institutions and many of the individuals in those institutions who were charged or appointed themselves to disseminate that culture of commemoration, of memory with the humanistic message of ‘never again’ — never again what? Never again in humanity. Never again genocide. Never again indifference to human lives. They have been silent over what is happening in Gaza. They have not spoken out now for two years. And that, I think, has greatly diminished their authority. And I’m afraid the result of that may be that this culture of commemorating the Holocaust may recede back to where it began, which is a kind of ethnic enclave of Jews talking about their suffering with other Jews.”

Ray Thek is a pseudonym for a Myanmar writer who needs to remain anonymous.

Further reading:

80 years after Auschwitz: Milk the Holocaust but ignore Israel’s genocide

“Depopulating” Palestine: Israel Through the Bifocal Lens of Hitler and Lemkin

Live: ICJ rules on Germany’s complicity in Israel’s alleged genocide in Gaza | DW News

Comments

Post a Comment